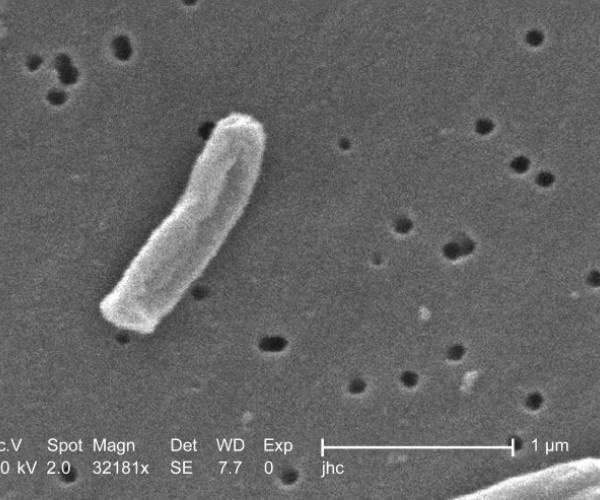

Seas and oceans invaded by bottles, saucers, glasses, straws and shopping bags. Fish and birds killed by excess plastic ingested or filtered through gills. Idyllic beaches awash in garbage that will take centuries to dispose of. These are disturbing scenes, to say the least, that the media have been proposing for several months in an effort to raise awareness of the environmental disaster for which we have “unknowingly” made ourselves responsible and the urgent need to remedy. Before our health also loses out. But it is not only the macroscopic plastics abandoned in nature that we need to worry about. The microparticles released from beverage and food bottles and containers and the plastic fragments that may be present, albeit invisible, in the drinking water that flows from taps and that we take in without realizing it also deserve much more attention and more research than has been done so far. This is highlighted by the World Health Organization (WHO) in its recent Report “Microplastics in drinking-water,” which takes stock of the state of scientific evidence on the subject. In summary, although currently available data do not indicate significant risks to human health from microplastics present at low levels in drinking water, WHO believes there is an urgent need to undertake new studies on this issue and to immediately activate policies aimed at curbing the production and use of plastic items to avoid exacerbating the already critical environmental damage. The Report reassures that plastic fragments larger than 150 µm (invisible to the human eye) that may be present in drinking water and in foods to which it is added during preparation are not absorbed by the intestines and should, therefore, not have a metabolic impact. Smaller particles may, on the other hand, enter the body, but the average amount absorbed should still not be a health detriment. On the other hand, the conditionalities are many and the certainties few, partly because the problem is relatively “new,” because standardized methods for measuring human exposure levels to microplastics have not yet been developed, and because any adverse effects may only manifest themselves over the long term or in a manner that is not clearly referable to a single material or compounds derived from it once absorbed by the body (catabolites). While waiting for new useful data, WHO suggests treating drinking water and sewage with purification systems already in use to remove various chemical agents and pathogens responsible for gastrointestinal diseases, which can also remove microplastics, protecting both humans and the environment. Proper filtration of wastewater, for example, can remove up to 90 percent of the microplastics present. Unfortunately, not all areas of the world have these purification systems nor do they have the ability or sensitivity to invest in actions that protect the environment. As much as this is a global problem, which needs to be addressed at the policy level as well as the scientific level, everyone can help reduce the impact of large and small plastics on the environment and human health by: choosing alternative, easily biodegradable/recyclable and health-safe materials as much as possible; preferring items that can be reused for a long time instead of single-use; sorting items properly; and never abandoning waste in the environment.

Source: Microplastics in drinking-water. Geneva: World Health Organization 2019. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

Photo by Jasmin Sessler on Unsplash