After decades of underestimating the unfavorable effects of pollution on human health, studies and evidence on the subject have been multiplying for some years now, unfortunately all of them directed toward confirming what has always been feared in science: the environmental pollutants have direct detrimental effects at multiple levels (in particular, on the cardiovascular system, the nervous and immune systems, the reproductive level, etc.) and, even when not properly harmful, can alter the metabolic balance in various ways.

Among the many researches supporting this claim, two recent ones can be mentioned. The first, conducted at the University at Buffalo (U.S.), assessed the change in the levels of 886 metabolites in the human body before, during and after the Beijing Olympics (China, 2008): three moments when environmental pollution in the city and surrounding areas went, first, from very high to low (thanks to government actions aimed at making the air more acceptable during the competitions), then from low to the same very high pre-Olympics levels.

Metabolomics analysis of blood samples taken at each of these three periods from the more than 200 Beijing residents involved in the study indicated that as many as 69 metabolites normally present in the body increase or decrease in response to increased or decreased air quality. In particular, varying the most are lipid compounds (mono- and polyunsaturated fatty acids, branched fatty acids, steroids, etc.) and dipeptides (i.e., small proteins), which are often involved in the regulation of innumerable cellular, metabolic, and hormonal functions (in particular, cell stability, oxidative stress, antioxidant activity, and inflammation).

This type of metabolomic analysis, able to provide a snapshot of all the significant molecular changes induced by pollution in the human body, does not indicate which diseases may result from living in areas (urban or rural) characterized by low environmental quality, but confirms that pollution interferes with a great many physiological activities and provides the biological basis for explaining the link between the observed disorders (cardiovascular and metabolic diseases, cancers, immunological or hormonal alterations, etc.) and pollution.

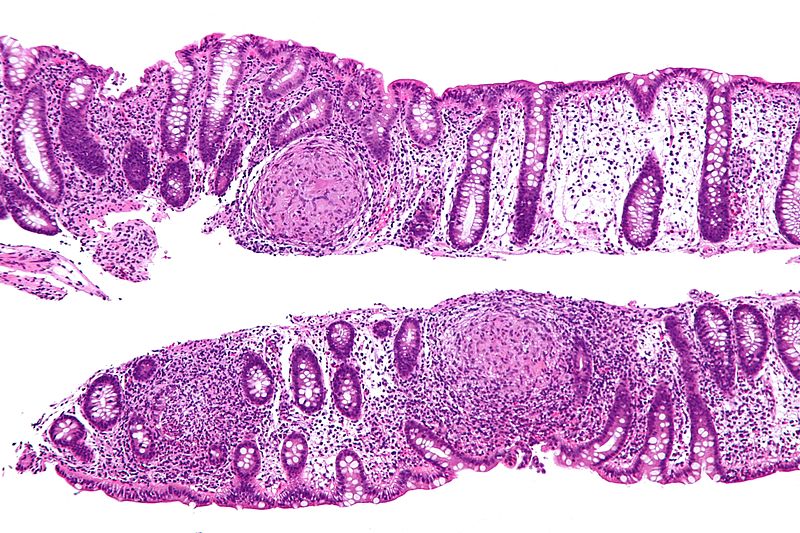

The second publication is even more alarming. This is a review and meta-analysis of data available in the literature on the effects of automobile pollution in children, with particular reference to the risk of developing leukemia (the most common cancer in the early years of life, the incidence of which has increased continuously since 1975 to the present).

The cross-validation of the 29 major studies on the subject, in which researchers from the University of Modena and Reggio Emilia also participated, indicated that car traffic pollution may actually increase the risk of pediatric leukemia only when very high. The same goes for nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels, a major component of exhaust gases along with benzene. Conversely, exposure to an aromatic hydrocarbon such as benzene (and its derivatives) has definite carcinogenic effects at any dose and always increases to some extent the risk of developing leukemia in children less than 6 years old (specifically, acute lymphoblastic leukemia, ALL).

Two findings that, combined with countless others in the literature, should prompt all of us, every day, to strive to reduce emissions and environmental pollution in general (using the car less, avoiding excessive home heating and producing more waste than strictly necessary) and to demand that governments take measures aimed at improving the healthiness of air, water and soil in both urban and natural areas. Because there is no doubt: our health depends on the health of the place where we live.

Sources

- Mu L et al. Metabolomics Profiling before, during, and after the Beijing Olympics: A Panel Study of Within-Individual Differences during Periods of High and Low Air Pollution. Environ Health Perspect. 2019;127(2):057010. doi:10.1289/EHP3705 (https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/full/10.1289/EHP3705)

- Orioli R et al. Exposure to Residential Greenness as a Predictor of Cause-Specific Mortality and Stroke Incidence in the Rome Longitudinal Study. Environ Health Perspect 2019;127(2):27002. doi:10.1289/EHP2854 (https://ehp.niehs.nih.gov/doi/full/10.1289/EHP2854?url_ver=Z39.88-2003&rfr_id=ori:rid:crossref.org&rfr_dat=cr_pubpubmed)