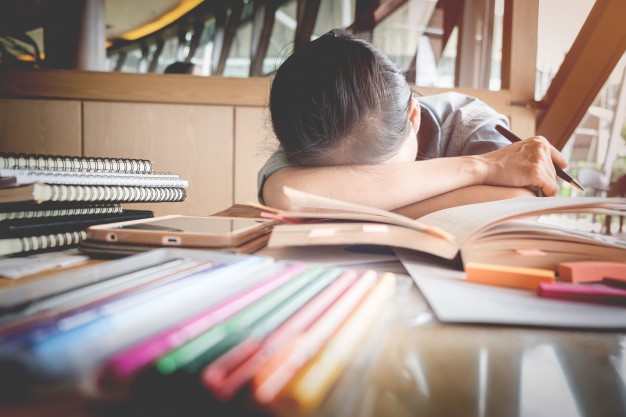

Adolescent mental health is causing no small amount of concern globally. Studies conducted from the 1980s to the present indicate a gradual increase in the prevalence of psychiatric distress, which can undermine peaceful psychoemotional growth and the building of positive interpersonal relationships: two fundamental elements, at this delicate stage of life, for developing a “solid” personality, achieving a good inner balance and maintaining a satisfactory quality of life in adulthood.

In particular, becoming increasingly common seem to be so-called “internalization” or “introjection” symptoms, i.e., feelings and behaviors indicative of inner or internalized suffering that is not actively or immediately expressed outwardly. For example, the following are symptoms of internalization: avoiding interaction with others; speaking little and shutting oneself in; feeling lonely and unloved/considered; being nervous and irritable; worrying excessively; suffering from discomfort not referable to an organic cause (such as headache, stomach ache, etc.); not being able to concentrate; feeling sad, low energy or down; lacking interest in most things/situations; sleeping or eating more or less than usual. Some, perhaps, will recognize in this list the typical picture of depression and anxiety. And he is not wrong, because the onset of these manifestations, in many cases, is a prelude to the very clinical diagnosis of these psychiatric disorders, which are also increasingly found among adults.

To delve deeper into the phenomenon, specify its characteristics and hypothesize its causes, a group of Swedish researchers from Umeå and Stockholm Universities analyzed how the incidence of psychiatric symptoms among adolescents has changed over 30 years by comparing two cohorts of students, residing in two medium-sized industrial towns in northern Sweden, who were attending the last year of compulsory school in 1981 and 2014. Each cohort, consisting of 1,083 and 682 boys and girls, respectively, was asked to answer identical questionnaires based on 4 scales assessing depressive, anxiety, and functional-somatic symptoms (i.e., related to physical complaints of possible psychic origin).

The comparison showed that from 1981 to 2014, the prevalence of internalizing disorders actually increased significantly in adolescents of both sexes, but particularly markedly among girls. Conversely, so-called “conduct disorders” (i.e., aggressive and violent attitudes, bullying, risky behaviors, etc.) have decreased among boys, while they have increased among girls, equalizing the prevalence between the two sexes and leaving the overall prevalence figure almost stable compared to 30 years earlier. The researchers also found that there was no obvious correlation between sociodemographic factors (family income, living environment, etc.) and adolescents’ psychiatric symptoms, with the only exception being a higher prevalence of conduct disorders among 1981 teens who had unemployed parents.

The underlying causes of the increase in depression and anxiety symptoms among teens remain to be determined, but the study authors believe that some profound socioeconomic changes since the 1990s may have played a role, even when they did not directly affect adolescents. The main ones include: the extremes of the liberalist economic model and its repercussions on the labor market (flexibility, job instability, driven competition, increased demands, reduced rewards, etc.); the deterioration of social relations and sense of community; family economic difficulties and uncertainty about the future resulting from the crises of recent years; technological evolution and the “virtualization” of interpersonal relationships through social media, resulting in isolation, distortion of perception of reality, and online frustration/harassment; and concern about one’s own future and that of the planet, which are increasingly difficult to predict and less and less rosy to assume.

According to the authors, in order to curb the phenomenon and ensure adolescents and adults greater psychoemotional well-being, it is necessary not only to recognize and address the symptoms of depression and anxiety on the level of “medical” prevention, but also to consider all the mentioned contextual aspects and try to modify them in a more “psychologically acceptable” sense. Certainly not an easy undertaking and one that does not immediately translate into practice.

Source: Blom H et al. Increase of internalized mental health symptoms among adolescents during the last three decades. Journal of Public Health 2019;29(5)925-931(doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckz028)

Photo by Kyle Broad on Unsplash