HOW TO RECOGNIZE IT

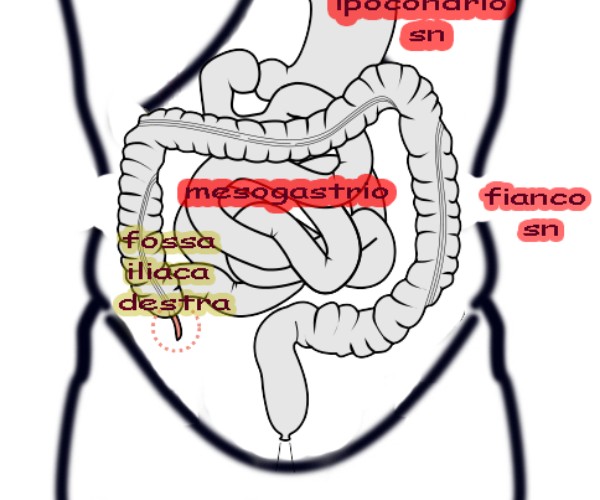

Acute gastroenteritis may manifest with diarrhea, vomiting, fever, anorexia, and abdominal cramps. Vomiting followed by diarrhea or the opposite occurrence may be the picture of onset in children. However, it is a nonspecific sign, and when it is the only initial manifestation, other possible conditions such as urinary tract infections, meningitis, gastrointestinal obstruction, and ingestion should not be excluded. Characteristics of vomiting, such as color, intensity and frequency, as well as relationship to meals, can often suggest the most likely diagnosis.

ASPECTS TO BE EVALUATED AND REPORTED

Daily number of episodes of vomiting and/or diarrhea, diuresis, presence of blood in stool, associated symptoms such as fever, abdominal pain, and urinary tract disorders, recent fluid and food intake, recent medication intake, and child’s vaccination history, contacts (any similar cases), return from travel.

CAUSES AND MECHANISMS

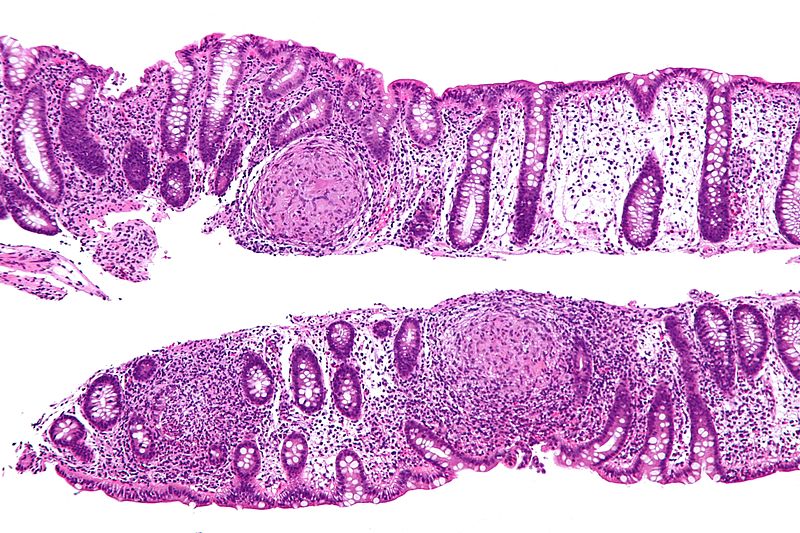

Globally, viruses are the major contributors to cases of acute gastroenteritis in children (about 70 percent), with Rotavirus being the best known (among other things, the specific vaccine is available), while among bacteria, Salmonella, Campylobacter and Escherichia coli stand out, depending on location and circumstances (Table). Unfortunately, only in a minority of cases is it possible to identify the responsible agent through co-culture. In 10% of cases, acute diarrhea is sustained by different factors including for example allergies, medications (especially antibiotics) or toxins. Viral infections are usually characterized by low-grade fever and nonhemorrhagic watery diarrhea. Bacterial infections, on the other hand, may be associated with a high likelihood of high fever and blood in the stool.

Table

|

Virus: |

| Rotavirus

Norovirus (Norwalk-like virus) Enteric adenoviruses Calicivirus Astrovirus Enterovirus |

| Bacteria

|

| Campylobacter jejuni

Salmonella spp non-typhoid Enteropathogenic Escherichia coli Shigella spp. Yersinia enterocolitica Shiga toxin-producing E coli Salmonella typhi and S paratyphi Vibrio cholerae |

| Protozoa

|

| Cryptosporidium

Giardia lamblia Entamoeba histolytica |

| Elminti |

|

Strongyloides stercoralis |

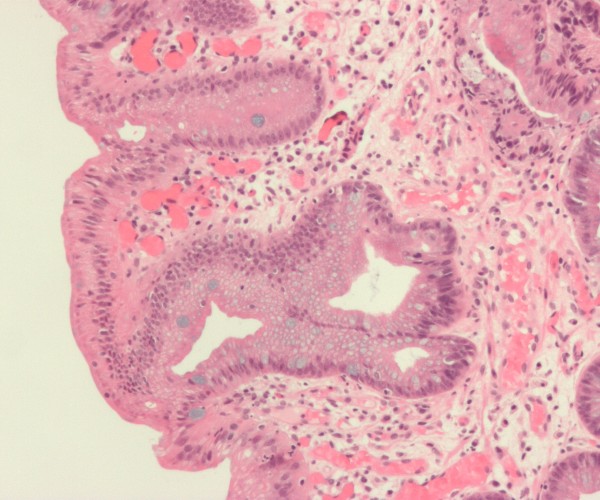

The Rotavirus

So named because of its wheel-like appearance under the microscope, it affects the stomach and intestines and is the leading cause of pediatric gastroenteritis cases reported each year in Italy. In particular, it is estimated that it infects nearly all children by age five, of whom one in four is less than six months old. Rotavirus has an incubation period of only two days, is highly contagious and spreads easily, especially in enclosed environments: it enters the body through ingestion of contaminated water or food (i.e., orofecally), but can be transmitted from one person to another through hands or contact with toys, dishes or accessories. In young children, rotavirus, which carries a more fearsome impact with the first infection, can cause a major form of diarrhea, with fever and vomiting lasting 3 to 7 days. The resulting loss of water and minerals can lead to severe dehydration and necessitate prompt hospitalization. Rotavirus can persist for several days on contaminated items, and hand hygiene and disinfection of exposed surfaces, although useful and desirable, are hardly sufficient to prevent infection. Vaccination, administered orally and recommended by all scientific societies, is therefore the best strategy to protect infants and young children, as early as six weeks of age. It is safe and can cut hospitalizations by 80%, as well as reduce outpatient visits and infection costs.

CARE AND PREVENTION

Assuming that most of the time it is not possible to intervene on the cause, the treatment of acute gastroenteritis consists of two phases in which the continuous fluid losses due to vomiting and diarrhea must be constantly compensated:

- rehydration and maintenance. In the rehydration phase, fluid supplementation should be done rapidly, over the course of 3-4 hours, using Oral Rehydration Solutions (ORS). In the maintenance phase, calories are usually given in addition to fluids.

Rapid rehydration should be followed by rapid reintroduction of nutrition, with the goal of quickly returning the child to an age-appropriate free diet. Breastfeeding should continue during both the rehydration and maintenance phases.

The decision to hospitalize the patient with acute gastroenteritis must take into account risk factors that predispose to unfavorable outcomes, such as: prematurity; lack of access to a health care facility for urgent needs and follow-up visits and other unfavorable socioeconomic factors; intractable vomiting; poor tolerance or refusal of ORS therapy; severe dehydration (defined as loss of more than 10 percent of body weight); age less than 1 year; irritability, lethargy, or uncertain diagnosis that may require close observation; presence of other diseases (comorbidities) that may complicate the clinical course; failure of ORS therapy, including aggravation of diarrhea and dehydration despite appropriate ORS administration.

Prevention relies on adherence to hygiene rules (hand washing, especially after using toilets and everyday objects, attention to proper food preparation and storage) and, with regard to Rotavirus, vaccination, which is recommended from the age of six weeks.

Types of preparations

Various solutions are available that can help limit water loss and promote the healing process and balance the gut, including:

- adsorbent substances, so named because they “absorb” bacteria and related toxins, promoting their elimination, and reduce the duration of diarrhea;

- antisecretory preparations, which reduce fecal water loss and affect the duration and severity of diarrheal episodes;

- probiotics, which are useful in rebalancing the intestinal flora, altered as a result of the infectious event, and effective in reducing the duration of diarrhea and the number of discharges;

- Medical devices to restore the condition and physiological function of the intestines.

Functional disorders

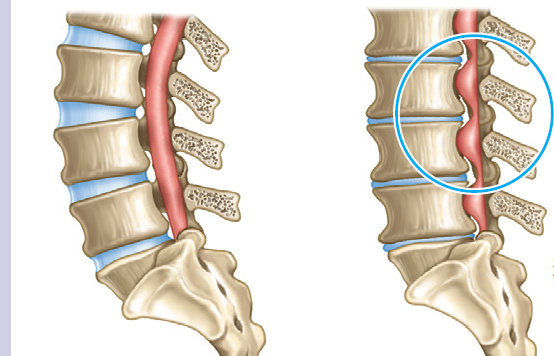

Gastrointestinal functional disorders cannot be traced to specific abnormalities and are therefore enigmatic, not easily negotiable and uninterpretable: sometimes they are regarded as psychological disorders, while in other circumstances their existence is even denied or they become a pretext for investigations aimed at documenting organic alterations but completely expensive and useless. In the absence of diagnostic markers, a multidisciplinary approach is essential, giving due consideration to family and environmental influences, events in the child’s history, infections, and major losses. A functional gastrointestinal disorder can thus be considered as the effect of the interaction between psychosocial factors and altered gut physiology, mediated by the gut-brain axis. Psychosocial factors, then, can affect the intensity of gastrointestinal symptoms: for example, strong emotions or stress produce increased motility in the esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and colon. Indeed, children with these disorders are characterized by increased motility in response to stressful agents (physiological or psychological) and have, among other things, a lower threshold of pain perception (called visceral hyperalgesia) or increased sensitivity to pain (allodynia). The demand for medical care depends on the parents’ level of concern, which in turn stems from their own experiences, lifestyle, expectations and perception of the disease. Among other things, overtreatment is not uncommon, which can promote a fragile condition and hinder the child’s proper development. For this reason, it is important to explore not only the child’s symptoms but also the fears, conscious and unconscious, of his or her parents and the repercussions that environmental, dietary, psychological, and behavioral factors may have on the course of the disorders.