Placebo effect and its opposite nocebo

The oldest and most spectacular episode of alternation, in the same person, of a placebo effect and its opposite nocebo, published in the scientific literature, is the one described in 1957 by Bruno Klopfer, a German psychologist. A gentleman named Wrigth, suffering from advanced-stage cancer, asked his attending physician to be treated with an experimental drug. After a single injection, “the tumor melted away like a snowball on a hot stove,” the doctor wrote in the medical record. A short time later, Mr. Wright, now recovered, casually read an article that discussed the ineffectiveness of that drug in tumors. Wright worsened within a few days. On examination he presented metastases. At that point the doctor injected the patient with water, telling him that he had received a new version of the drug that was effective this time. The metastases disappeared!

We do not know how Herr Wright’s story turned out, but we do know that in the last fifty years more than a hundred clinical and experimental papers have been published to try to understand what is incontrovertible: the occurrence of positive or negative effects in the physiology of a person who has been given fresh water believing it to be a drug, or who has been the subject of good or bad words. Martina Amanzio, of the Turin School of Psychology, and Fabrizio Benedetti, also from Turin, Italy, and an international authority on placebos, reviewing studies that have tested anti-hemicrania drugs, recorded that in the placebo group the frequency of adverse effects is high, which is not supposed to happen with taking inert pills; but the most intriguing part of the story is that the adverse effects are the same as with the drug tested. And that is, in studies that tested anticonvulsant drugs, the placebo group showed anorexia and memory impairment, the typical adverse effects of anticonvulsants. Thus, in studies that tested nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (the NSAIDs), the prevalent adverse effects were nausea and gastrointestinal complaints, which are typical of these drugs.

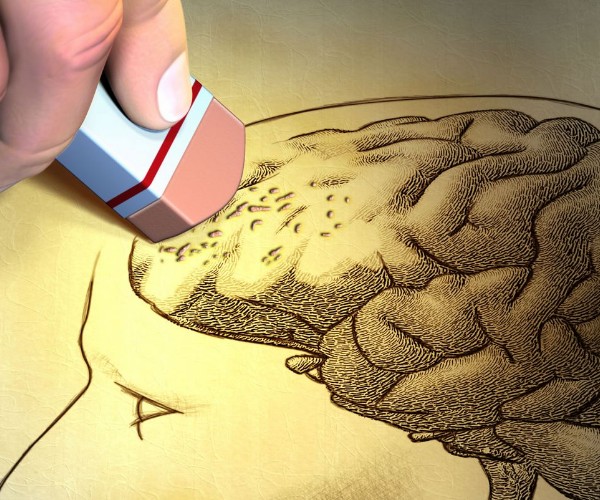

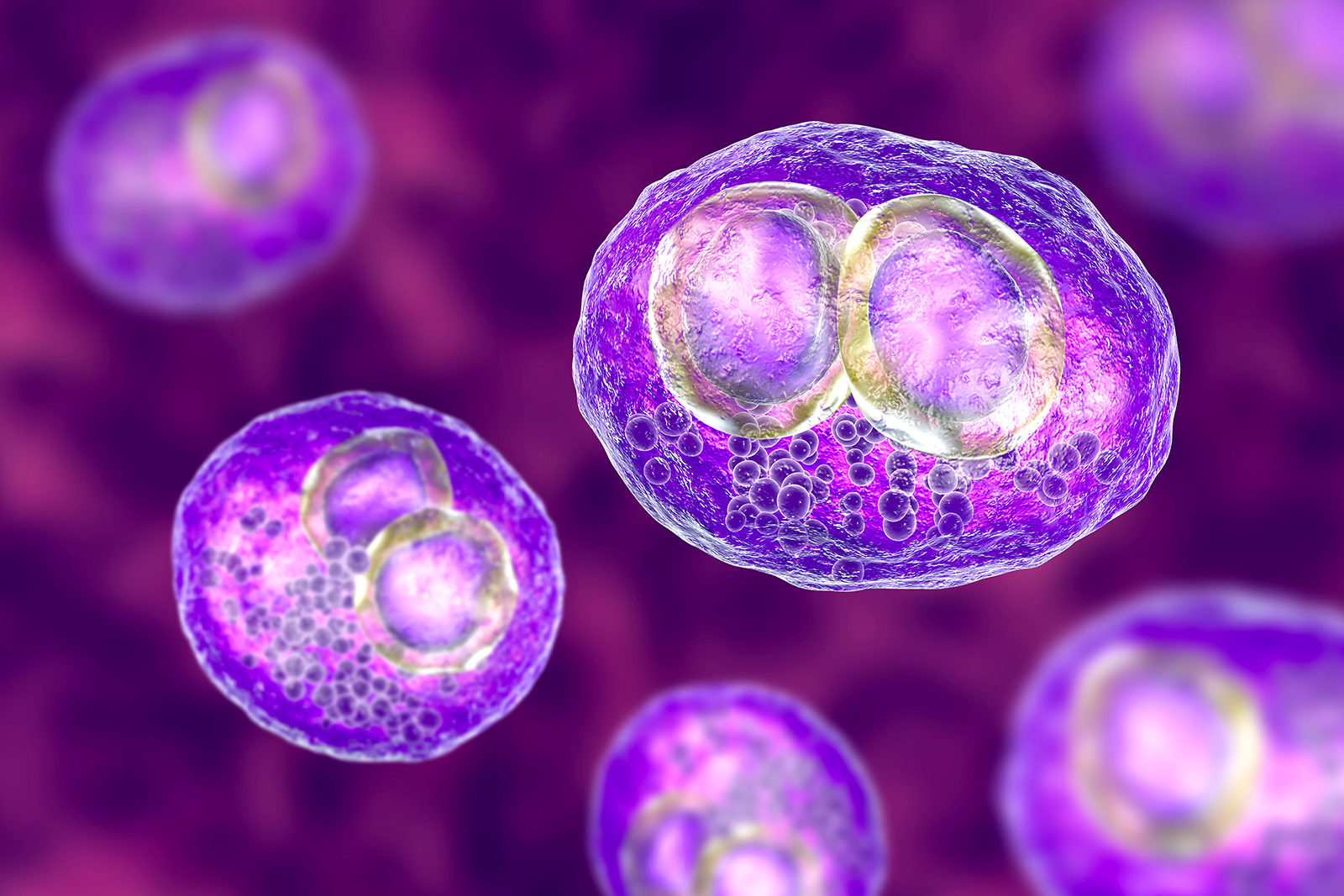

The explanation for this phenomenon lies in the expectations of people, who were (correctly) informed about the possible side effects of drugs: information and ‘expectation produced the peculiarity of the symptoms. But it is not just a matter of expectation. The first animal study to show the influence of a placebo on the immune system was that of Robert Ader, a pioneer in psychoneuroendocrinoimmunology: in 1975 he showed that rats conditioned by taking saccharin combined with a potent immunosuppressant (cyclophosphamide), even when receiving only saccharin manifested signs of immunosuppression. Thus, there are forms of conditioning that do not reach consciousness and still produce effects. This is also why there is interest in possible clinical use of the placebo effect. Benedetti showed that it is possible to produce a positive placebo effect in Parkinson’s patients by prolonging the effects of drugs with placebo pills, or in sportsmen by prolonging, by the same means, the effects of a narcotic drug. But what happens in our brain? The application of neuroimaging techniques has demonstrated the existence of a dual pathway: one for placebo and the other for nocebo. The former activates the so-called reward and pleasure circuit, the latter the anxiety circuit. The former relies on dopamine and opioid activity, the latter on cholecystokinin activity.

Expectancy reduces pain

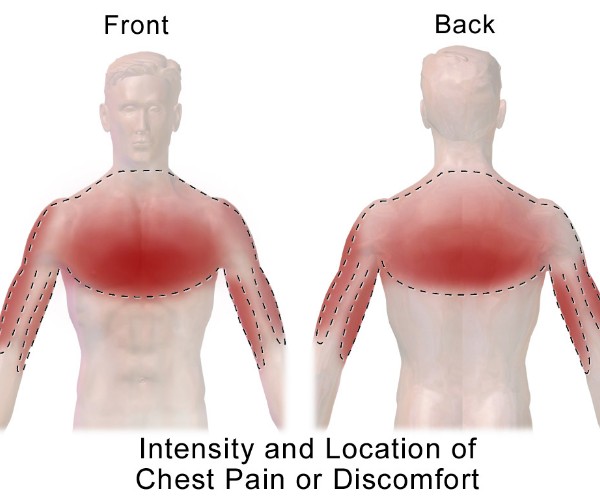

It has been documented for a number of years that expectation-and thus the value the subject places on an impending painful event-conditions the level of intensity with which it is perceived.

For example, if a source of heat is applied to the same subject that is reported to be of a lower degree than previously applied, this expectation reduces the activation of brain areas involved in the reception and decoding of pain, and thus, although the subject has received an intense painful stimulus (50 C° heat in one hand), he or she perceives it as less intense, or, rather, as intense, as he or she expected it to be (48 C°).

By Francesco Bottaccioli