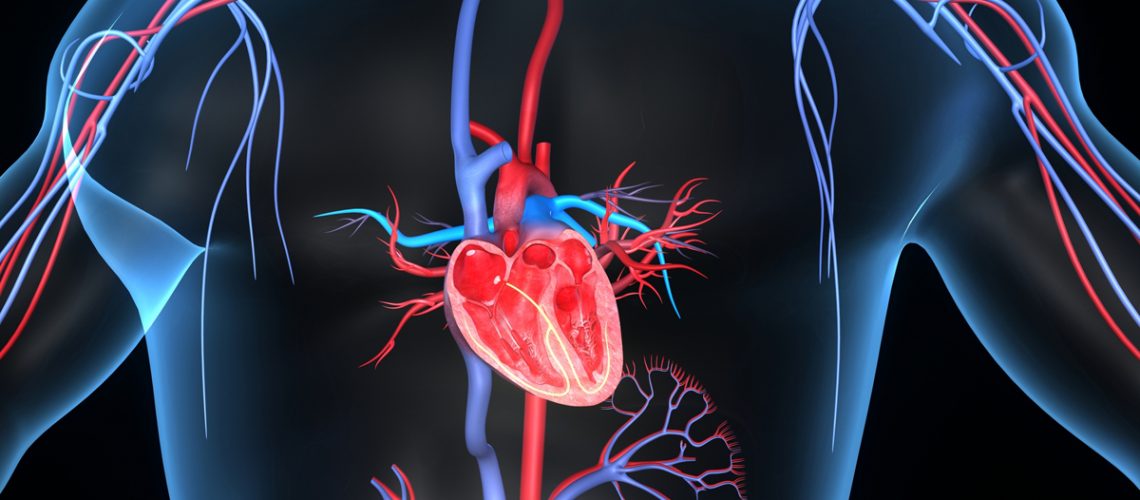

Poisoning can also cause cardiovascular collapse; in fact, antidepressant drugs can trigger cardiac arrhythmias, consequently altering cardiac output.

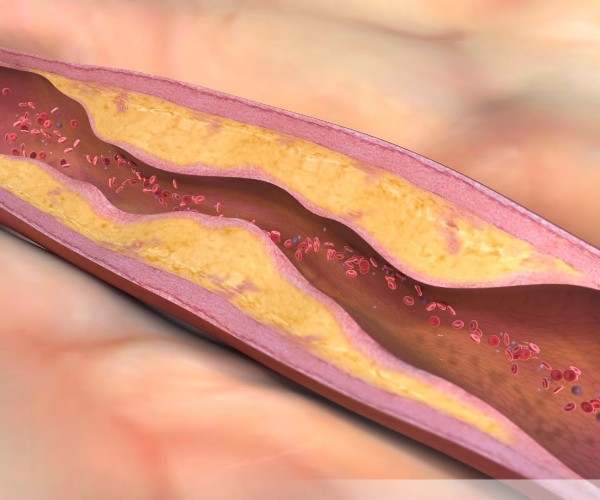

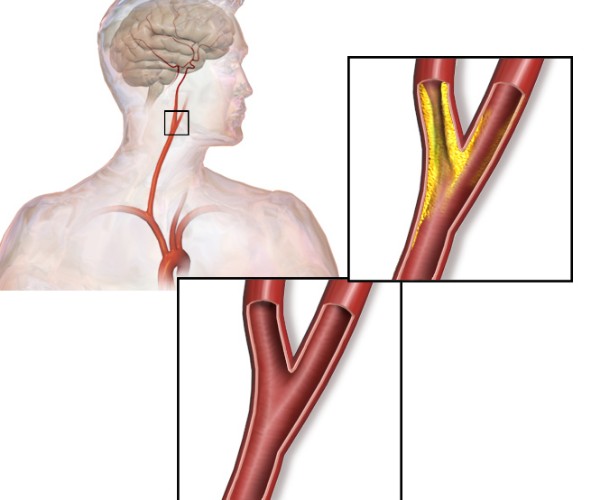

It is necessary, therefore, to measure blood pressure and heart rate at regular intervals and frequently, so that continuous ECG recording is made. Shock, in the poisoned patient, is almost always an expression of a disproportion between the capacity of the vascular bed and the volume of blood contained in it. Venous return, for this reason, decreases by having a reduction in cardiac output.

Cold, pale, moist skin is the real wake-up call. When the systolic blood pressure value falls below 90 mm Hg, action must be taken. The treatment first involves walking up the bed to increase venous return to the heart. If this measure is not sufficient, it is absolutely necessary to expand the circulatory volume intravenously. If even then the patient tends not to recover, then the use of intropi drugs is justified. Cardiac arrhythmias may disappear once the anoxia and acidosis are corrected. Antiarrhythmic therapy should be used only when rhythm changes are such that cardiac output is seriously impaired.

Source: Roy Goulding’s Vademecum of Poisoning Therapy.