In our experimental studies, we observed that subjects who have been practicing Yoga for a long time easily tend to breathe more slowly. Many practitioners spontaneously adopt the three-stage breath, which, on inhalation, mobilizes first the diaphragm, then the lower chest and then the higher chest. These people, when they breathe oxygen-poor air, are able to maintain relatively little increased ventilation, but at the same time they take in more oxygen, unlike non-practitioners who must ventilate much more to achieve the same result.

Yoga practitioners therefore have greater ventilatory efficiency and have a marked reduction in the stimulus to ventilate induced by oxygen deficiency. We have also observed this phenomenon in Himalayan populations, an example of effective adaptation to the lack of oxygen present at high altitude, who seem to spontaneously adopt this type of three-stage breathing. We have also observed that yoga practitioners, probably as a result of training, tend to maintain this characteristic over time.

A confirmation of this reasoning comes from our observation of the mountaineers on the recent 50th anniversary expedition to conquer K2. The climbers who reached the summit without the need for oxygen had far less ventilation before they started their final ascent than those who, on the other hand, did not reach the summit or who had to use oxygen to reach it.

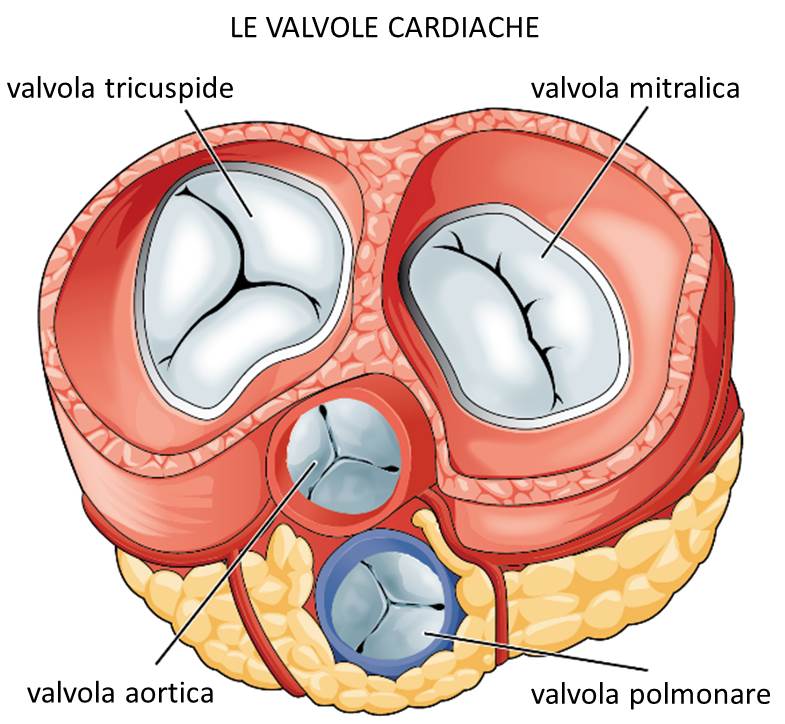

The practical consequences of these studies could be important. Yoga practice over time produces an improvement in breath efficiency, reducing ventilatory stimuli and improving control of the circulatory system, with a reduction in sympathetic activity and an increase in vagal tone. In heart failure, for example, both of these factors are very important. Therefore, it seems useful to combine breath control techniques with traditional drug therapy.