Logic would dictate that what triggers food allergies. was the simple ingestion of a food containing substances (usually, proteins, peptides or particular sugars) toward which the individual immune system reacts abnormally, recognizing them as potentially dangerous and activating a whole series of defense mechanisms to try to eliminate them from the body or, at least, to neutralize their action (in fact, in itself completely harmless).

In fact, when a food to which one is allergic is ingested, the immune system initiates reactive processes such as the synthesis of histamine (on which depend the onset of oozing, red patches, rashes of various types, swelling and itching in various parts of the body) and the production of immunoglobulin E (IgE, which trigger and sustain the allergic response in various organs and tissues), to the point of triggering, in the most severe cases (fortunately rare), an anaphylactic reaction, characterized by skin reactions, bronchoconstriction, angioedema (especially in the face and throat), hypotension, and anaphylactic shock with possible onset of coma, sometimes fatal.

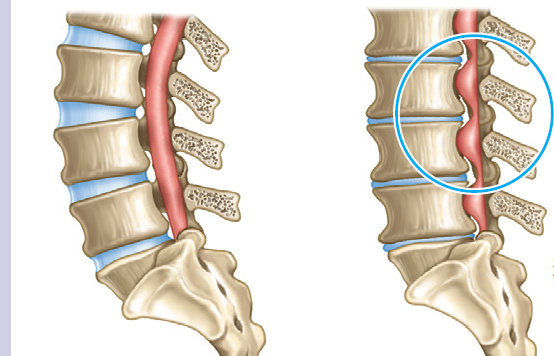

A study recently conducted in animal models (specifically, mice) has, however, indicated thatfood allergy could be linked to or, at the very least, be made more likely not only by the ingestion of certain foods, but also by stresses on the skin, such as those typical of scratching.

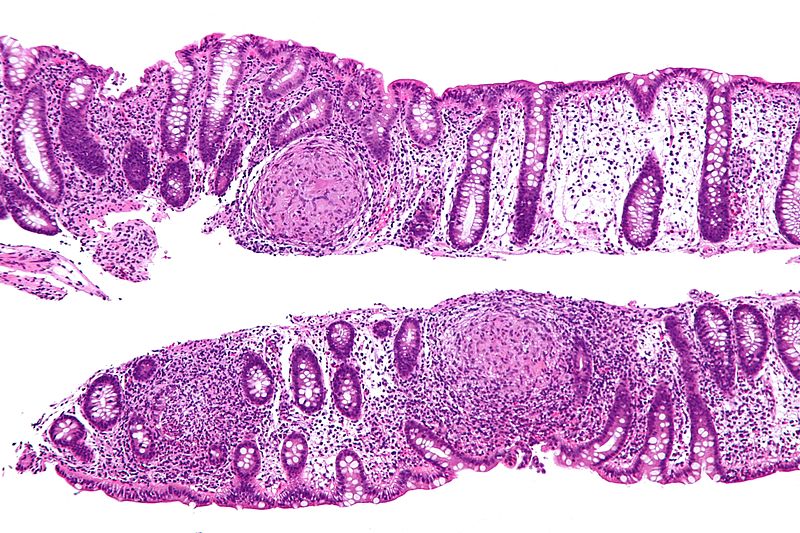

In particular, it has been observed that by mimicking scratching through the application and tearing of patches from the skin of mice, it is possible to trigger/increase intestinal reactivity to food allergens on the part of the animals, making them more likely to go through the typical symptoms already mentioned after ingesting food that is in itself completely harmless.

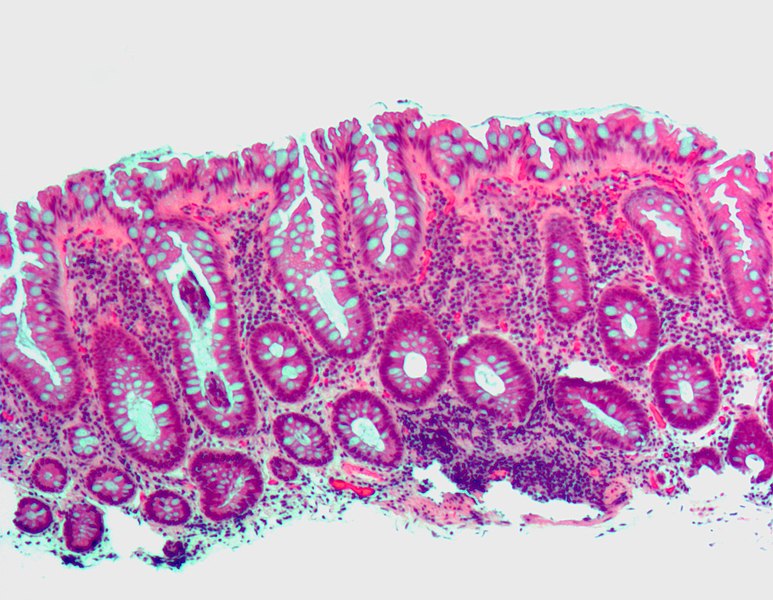

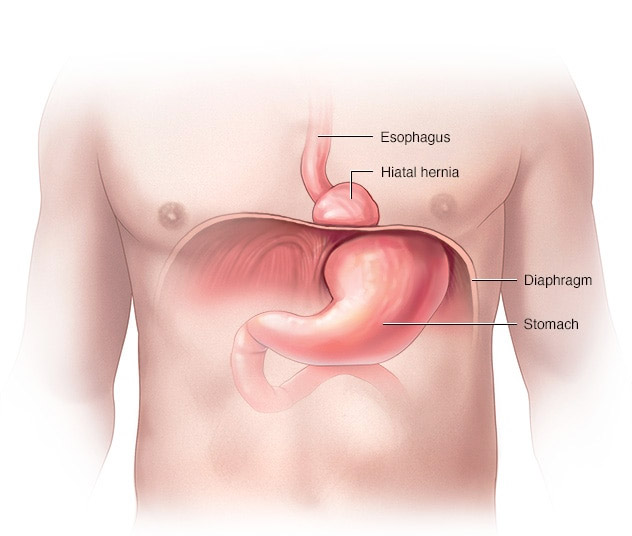

At the origin of this effect there would be a molecular link between the skin and the intestinal epithelium: repeated skin rubbing would trigger the release of a substance called interleukin 33 (IL-33), which, together with IL-25 produced by particular cells of the intestinal epithelium (tuft cells or “tuft cells”), would go on to stimulate a subset of immune system cells called innate lymphoid cell type 2 (ILC2) cells. The latter, through the release of IL-4, would stimulate other cells of the immune system called mast cells, which, in turn, would release mediators capable of increasing intestinal permeability to food allergens and, therefore, their absorption, resulting in an increased risk of leading to systemic allergic reactions and anaphylaxis.

If this initial evidence is confirmed in humans, the newly identified allergic communication and elicitation mechanism could explain why those with atopic dermatitis (a condition associated with skin discomfort and a tendency to repeated scratching) are more likely to also develop food allergies.

Source

J-M Leyva-Castillo, C Galand, et al. Mechanical skin injury promotes food anaphylaxis by driving intestinal mast cell expansion. Immunity 2019; doi:10.1016/j.immuni.2019.03.023 (https://www.cell.com/immunity/fulltext/S1074-7613(19)30140-2)