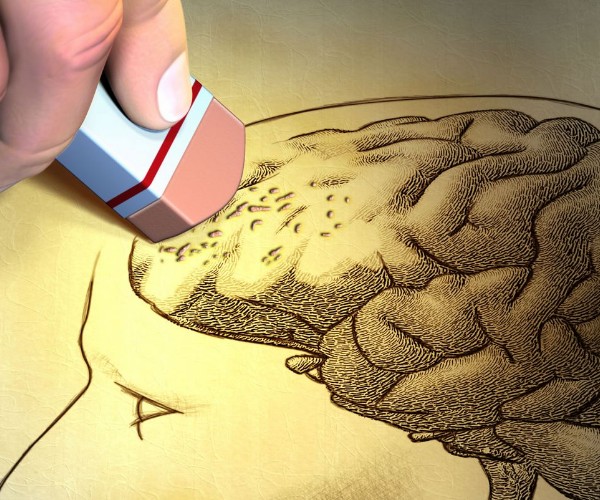

An interesting study recently published in the prestigious journal Nature points out how, to “build and maintain a complex brain,” our ancestors used nutrients found primarily in meat: iron, zinc, vitamin B12 and fatty acids. This is at the expense of plant-based foods that, while containing them, are still less rich in them. A diet low in meat, therefore, would expose one to risks of deficiencies in nutrients that are essential for the proper functioning of the central nervous system; on the other hand, it is now known that an excess of animal products has negative aspects, as it can promote serious chronic-degenerative diseases, such as cancer or cardiovascular disease, for example. Therefore, there must be a delicate balance in nutrition as well, and this is especially true in the very early stages of life, especially in the period between conception and the age of 2 years.

The most important nutrients

Two nutrients deserve special attention, precisely because they are strongly involved in brain development and, therefore, indirectly in memory as well: long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids (LC-PUFAs) and iron.

LC-PUFAs regulate the fluidity and enzymatic activities of cell membranes. Among them, the effect of DHA is especially noticeable during the delicate period when the nervous system of the fetus and infant/infant is formed: it preferentially accumulates in the frontal cortex and retina, thus assuming a key role in the structural development of the brain. It has been reported that infants fed formula containing DHA have better eye and motor coordination, greater concentration and higher scores on intellectual tests, and better logic skills. DHA and in general and LC-PUFAs are therefore considered essential nutrients for the development and maintenance of memory during all stages of life.

Iron is the second essential micronutrient: in addition to being critical for oxygen transport to peripheral tissues, it is involved in the production of myelin (the sheath that surrounds nerve fibers) and the neurotransmitters dopamine and serotonin. Several studies report that its deficiency has negative effects on memory, learning, and social interactions. The periods most at risk are those of intense growth of the body, thus pregnancy and fetal development, childhood and adolescence. The effects are reduced spatial memory in adolescence, reduced attention, and worse cognitive performance, manifested by lower school performance, poor test performance, and increased irritability and restlessness.