A child who cries, who does not sleep, who complains of headaches, stomach aches, leg aches, who refuses to go to school or do other activities, who always seems disgruntled or uninvolved, who exhibits anxious or aggressive behavior, sudden learning difficulties or eating disorders. It is these manifestations that greatly disturb and alarm parents in alternating feelings of concern and helplessness, as well as sometimes annoyance or embarrassment.

They then try to find a solution, turning in the vast majority of cases primarily to the pediatrician. These, next to the dutiful search for a clear, defined and circumscribed organic origin of the problem should give space for the story (of the symptom or disorder, but also of the family situation, the quality of relationships, the particular moment they are going through, etc. etc.) of both the parents and the child himself if he is old enough. It would also be necessary to offer psychological counseling space primarily to the parents (possibly and preferably both) and secondarily also to the child himself, with the use of play or drawing and, in the case of older children, specific interviews or tests.

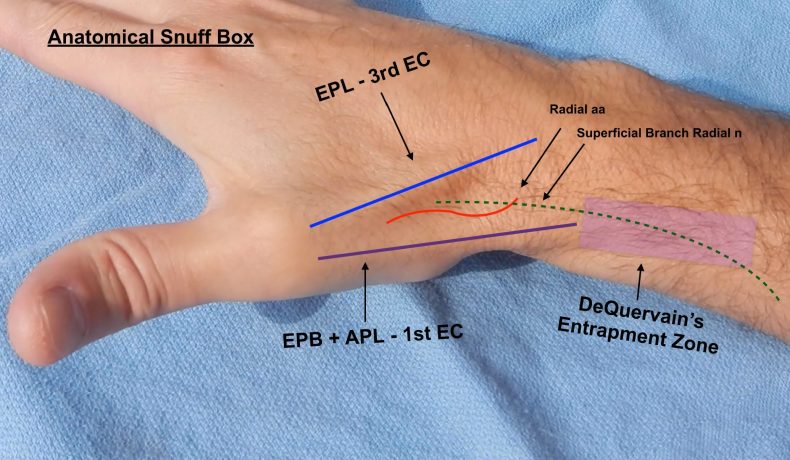

Counseling with parents aims to seek with them a hypothesis of the meaning of the disorder presented by the child, relating it to their history, relationship, expectations and fears. The dutiful starting assumption is that the disturbance or symptom is not something to be erased and eliminated but is instead an important message (of help, of attention, of affirmation, of difficulty, of reassurance) of which the child is unaware and which he expresses directly through his body and emotions. Already this represents an important and significant moment because it becomes a space of attention dedicated to him, in which parents are invited to take care of their child rather than worry about him, without delegating to the technician (pediatrician, psychologist, neuropsychiatrist) a “fine-tuning” intervention. Moreover, this allows the technician to accompany parents to cast a glance at their child, to understand how his or her development and manifestations mirror the relational map of the family and, for older children, the social environment. This space also provides an opportunity for parents to understand how the child perceives (and experiences) intra-family relationships, psycho-physical development, and what his or her ability to process distress is.

A bereavement, economic hardship, illness, family disagreements are all elements that imprint the emotional climate of a family, in which a child is totally immersed and like a sponge absorbs, processing it in its own way. How many times parents say “the child doesn’t know anything about it…we never talk in front of him!” as if the emotional climate depends only on the words and speeches made and is not something intangible that like smell, moisture are not controllable but are there. Children depend on their parents as their security, their point of reference, and when these securities falter, reactions can be the most varied. Of fear, of opposition, of giving up, of lowering immunity, etc.

Only if we can place the child’s manifestations in this more articulated and complex framework can we move beyond the narrow view of disease to accommodate a broader systemic and evolutionary view.