What does the gut microbiota have to do with a neurodegenerative condition such as Parkinson’s disease? Until yesterday, nothing, it was thought. Today, however, there seems to be a relationship, at least for those taking levodopa drugs to control tremors and muscle rigidity. That is, the vast majority of patients.

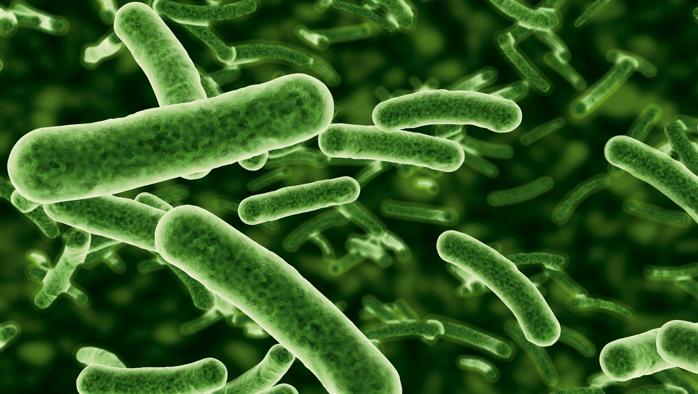

The role of gut bacteria

Intensive studies in recent years are teaching us that the gut microbiota serves as virtually everything, acting as an interface between us and the world and regulating countless enzymatic reactions and physiological functions. When healthy, everything is going well; when destabilized or depleted, the risk of seeing various ailments and diseases arise or worsen significantly increases.

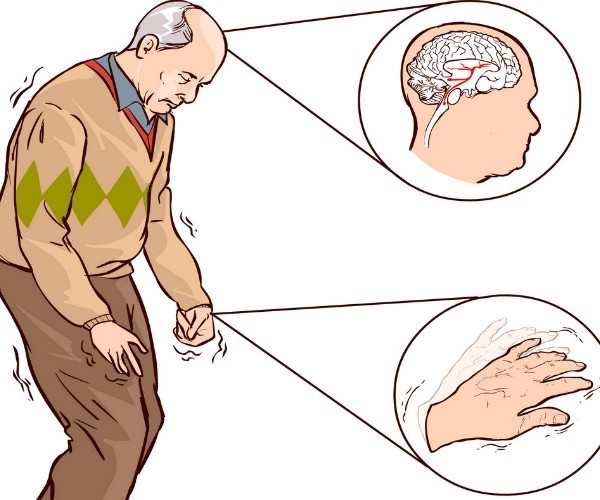

In the case of

Parkinson’s, the situation is somewhat different. Indeed, the characteristics and activity of patients’ gut bacteria do not create problems per se, but may interfere with the effectiveness of levodopa therapy: a dopamine precursor compound that must be constantly supplied from outside to replace dopamine no longer produced by the brain cells in the substantia nigra, degenerated due to the disease.

Levodopa is never administered on its own, but always in conjunction with a second substance called a “decarboxylase inhibitor,” which is essential so that levodopa is not rapidly converted into dopamine by the decarboxylases in the blood, but can reach the brain, where it must exert its action of modulating muscle tone.

It has been known for decades that, from the onset of the disease, different patients require different dosages of levodopa/inhibitors of decarboxylases to keep the symptoms of Parkinson’s disease under control and that, in all cases, the effective dosage gradually increases over time (due to a decrease in drug efficacy). Until now, however, no one could explain the reasons behind these phenomena.

New data on the effectiveness of therapy

A study recently published in Nature Communication suggests why this happens. In essence, the problem seems to be related to the ability of some intestinal bacteria (in particular, lactobacilli and enterococci, in which the constituent intestinal microbiota is rich) to transform levodopa into dopamine at the level of the small intestine, thus making it easily degraded soon after absorption and preventing sufficient amounts from reaching the brain.

Apparently, some Parkinson’s disease patients have a microbiota that is particularly active on this front, due to very high bacterial decarboxylase activity: this would make patients partially “resistant” to levodopa therapy, from which they might derive less than average benefits and gradually decrease over time.

Although it remains to be understood how to exploit these new data at the clinic-practice level, this is important information because it offers the possibility of improving and prolonging the efficacy of levodopa therapy by a different approach than those used so far, namely by modulating the composition of the gut microbiota and/or the activity of bacterial decarboxylases.

Source

Sebastiaan P et al. Gut bacterial tyrosine decarboxylases restrict levels of levodopa in the treatment of Parkinson’s disease. Nature Communications 2019;10:310. doi:10.1038/s41467-019-08294-y