The transition from daylight saving time to daylight saving time and vice versa causes some transient discomfort for many people, especially in terms of resynchronization of sleep-wake rhythms and mealtimes, fatigue or feeling slightly unwell/nervous during the day. Generally, for those with no health problems, everything works out in less than a week, the maximum period needed to realign one’s biorhythm to the legally mandated time.

For those with risk factors or specific diseases, however, changing the time every six months can result in far greater inconvenience. Numerous epidemiological studies have long indicated that the incidence of severe acute cardiovascular events (heart attack and stroke), as well as episodes of depression or anxiety in predisposed people, increases in the weeks after the hands of the clock move.

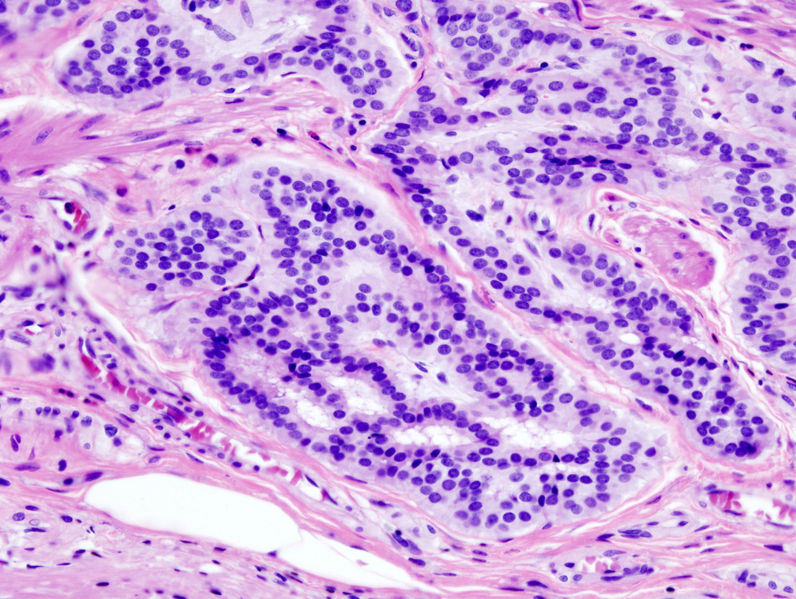

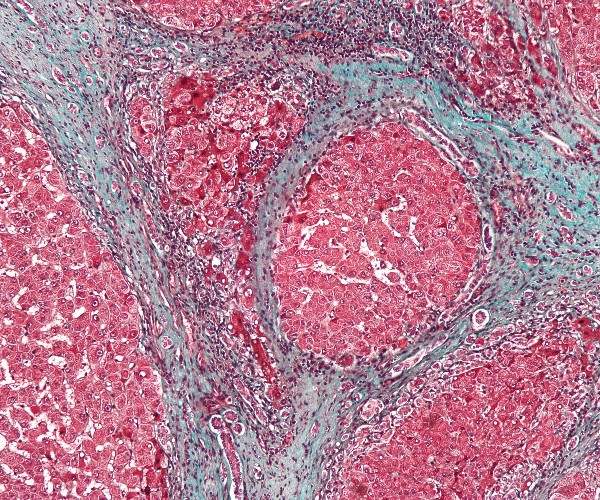

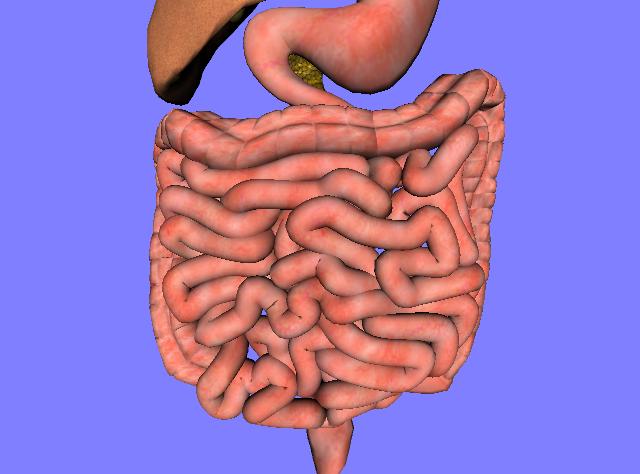

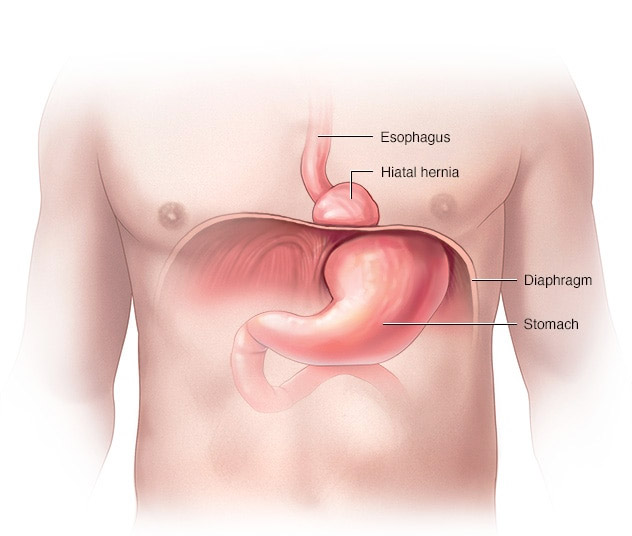

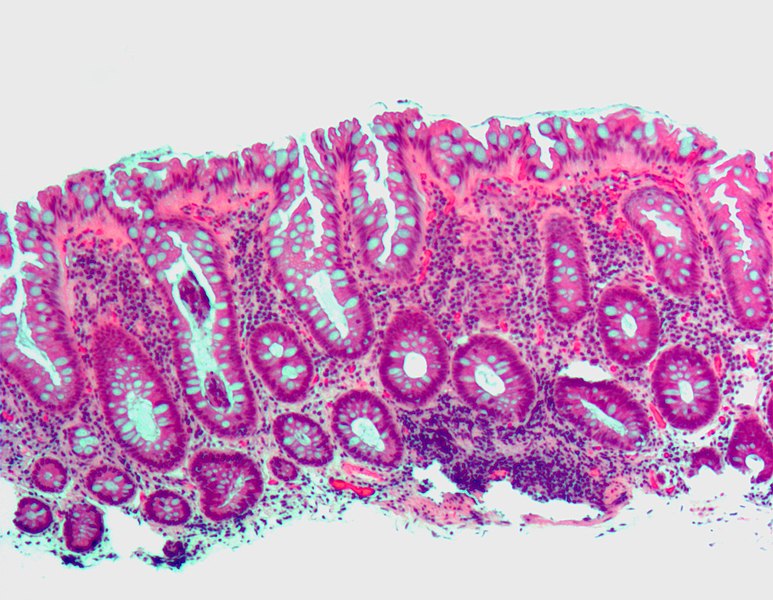

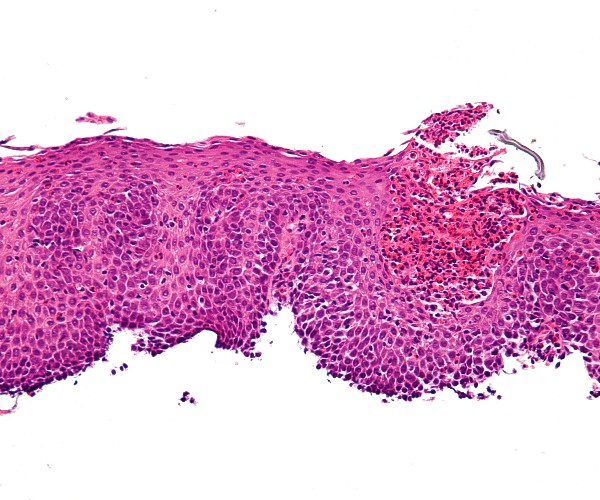

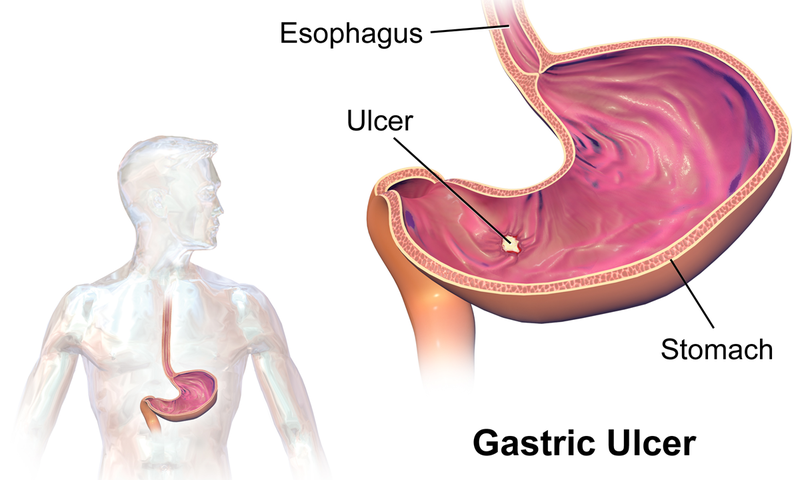

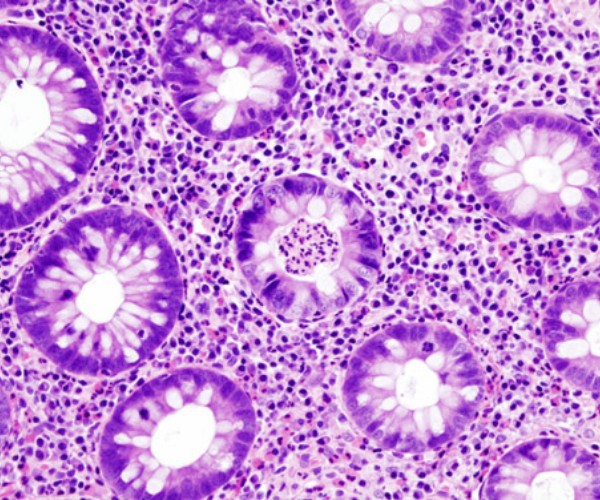

Recent data have, moreover, shown a correlation between the transition from daylight saving time to summer time and the risk of seeing worsen chronic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as ulcerative colitis and Crohn’s disease, with a significant increase in the number of flare-ups in the following 30 days in patients who were under control in the previous month. An observation entirely in line with the knowledge regarding the link between circadian rhythms and the regulation of gastrointestinal activity and the immune and inflammatory response.

In addition, it should be considered that the abrupt change in the amount of daylight to which one is exposed, resulting from the fake “time zone,” has a not insignificant impact on mood, and this aspect can also significantly affect the gastrointestinal symptoms of IBD or irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), which are also known to have a psychosomatic component.

Considering the considerable discomfort associated with IBD flare-ups (not infrequently disabling for several days/weeks), as well as the acute cardiovascular events already mentioned, and the expenditure of health care resources required to treat them, one frankly wonders whether it is ethically permissible and economically viable to continue to maintain the ritual change of the time twice a year, even in view of the now limited energy savings it makes in the face of the drastic change in the population’s living and working habits.

In Europe, the situation is expected to improve from 2021, when a recent decision by the European Commission envisaged the final switch to the single, year-round timetable. In other areas of the world, legislative changes along these lines have yet to be considered, to the detriment of those with health problems that may be exacerbated by a transient mismatch between the internal and external clocks.

Source Föh B et al. Seasonal Clock Changes Are Underappreciated Health Risks-Also in IBD? Front Med (Lausanne) 2019;6:103. doi:10.3389/fmed.2019.00103