Glaucoma has been called the “silent thief of vision.” This definition highlights the sneaky and ambiguous aspect of a degenerative disease affecting the optic nerve.

In glaucoma, as in all chronic and, especially at their onset, asymptomatic or paucisymptomatic diseases, the subject is confronted with an unexpected and unwelcome “guest” (the disease precisely), but what is more, it will become his or her “life companion.”

Indeed, the person who is diagnosed should primarily be accompanied and helped to adapt to a new state, physical and psychological, to adopt new lifestyles, and to integrate the disease into his or her identity.

The inevitable first reactions are of disbelief and denial, with feelings of anger, sadness or fear emerging.

These are common and normal reactions that are, however, and should remain transient, that is, not structured as permanent and constitutive elements of psychic functioning. For this they need recognition and processing.

The “host” represented by the disease in fact imposes a redefinition of self-image, boundaries and personal identity. After all, identity, let us remember, is not a static concept, a stable and fixed point of arrival once and for all, but is the product of continuous change determined by internal or external factors such as time, occasions, choices and, why not … illnesses!

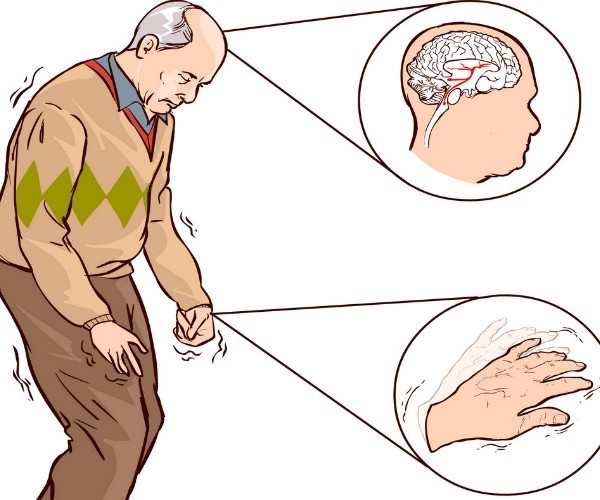

Furthermore, since the eyes are a key organ in movement choices, learning, reality control, and so many other daily functions, glaucoma can carry a significant burden in terms of existential consequences.

Indeed, it can result in:

- Depressive effects as a consequence of reduced self-sufficiency in home life and social relationships.

- Impatience with sometimes very complex therapy, based on the administration of several active ingredients at the same time, perhaps with different daily intakes

- Defiance following the use of famaci that lose their efficacy over time or present side effects.

- Psychological stress related to repeated and periodic assessments, some of which are also anxiety-inducing because they are performance-related (e.g., visual field).

The diagnostic and therapeutic approach is mainly aimed at controlling and curbing the values of the eye’s internal pressure and checking visual field capabilities.

Alongside this in the present day there is an orientation to give special attention to the patients’ lifestyle and level of psychological balance, since it is now accepted that the patient’s psychological health produces positive results in treatment and therapy and, especially how in chronic diseases, the patient is his or her own best doctor and his or her participation in and adherence to the treatment plan is crucial.

Therefore, the work of the caregiver should develop a specific focus on fostering in the patient the adaptation and acceptance of a new living condition, as well as providing detailed basic information about the disease that will increase awareness and provide greater ability to govern the disease.